Irish history spans over 5,000 years, from ancient megalithic sites to modern European prosperity. This rich historical tapestry has shaped not only the island nation but has influenced cultures worldwide through its diaspora. When planning your journey to the Emerald Isle, understanding Irish history provides profound context to the castles, museums, and landscapes you’ll encounter. This comprehensive guide explores the fascinating evolution of Ireland through the ages, highlighting key events and cultural developments that make Irish history uniquely captivating.

Ancient Ireland: The Dawn of Irish History (8000 BCE – 400 CE)

The story of Irish history begins with the first hunter-gatherers who arrived approximately 8000 BCE, following the retreat of ice sheets from the last Ice Age. These early inhabitants left their mark through the impressive megalithic monuments that still dot the Irish landscape.

Newgrange, older than both Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids, stands as a testament to the sophisticated understanding of astronomy possessed by Ireland’s ancient peoples. This 5,200-year-old passage tomb demonstrates remarkable engineering precision – during the winter solstice, a shaft of sunlight illuminates its inner chamber, an astronomical alignment that has endured for millennia.

The Bronze Age (2500-500 BCE) brought technological advancement to Irish history, with communities developing skills in metalworking and establishing trade networks across Europe. Archaeological discoveries from this period reveal elaborate gold ornaments and weapons, indicating a prosperous and stratified society.

Around 500 BCE, Celtic peoples arrived in Ireland, introducing their language (the foundation of modern Irish) and distinctive art styles. The Celts organized Irish society into a complex system of kingdoms and clans, with social hierarchies that included kings, warriors, druids, and craftspeople. Their cultural influence on Irish history remains evident in mythology, art, and language.

The La Tène culture (named after an archaeological site in Switzerland) flourished in Iron Age Ireland, producing magnificent metalwork characterized by intricate spirals and zoomorphic designs. The famed Broighter Gold Hoard, discovered in County Derry, exemplifies the sophisticated craftsmanship of this period in Irish history.

Early Christian Ireland: Saints and Scholars (400 – 800 CE)

The arrival of Christianity marks a pivotal chapter in Irish history. Traditionally credited to Saint Patrick in the 5th century, the transition from paganism occurred gradually but profoundly altered Irish society. Patrick, originally captured as a slave and brought to Ireland, later returned as a missionary and established Christianity throughout the island.

Following Christianization, Ireland entered what many historians consider its “Golden Age.” Monasteries became centers of learning, preserving classical knowledge while much of Europe descended into the Dark Ages after Rome’s fall. These monastic settlements played a crucial role in Irish history by serving as educational institutions, cultural repositories, and economic hubs.

Irish monks produced magnificent illuminated manuscripts, with the Book of Kells representing perhaps the pinnacle of this art form. Created around 800 CE, this incredibly detailed Gospel book features intricate Celtic knotwork and vivid illustrations, demonstrating the remarkable artistic achievement of early medieval Irish history.

The monastic tradition also drove a missionary movement that spread Irish influence throughout Europe. Irish monks established monasteries across the continent, from Iona in Scotland to Bobbio in Italy. Through these efforts, Irish scholars helped preserve classical literature and learning during a turbulent period of European history, earning Ireland its reputation as the “Land of Saints and Scholars” – a proud chapter in Irish history.

Viking and Norman Invasions: Reshaping Irish History (800 – 1200 CE)

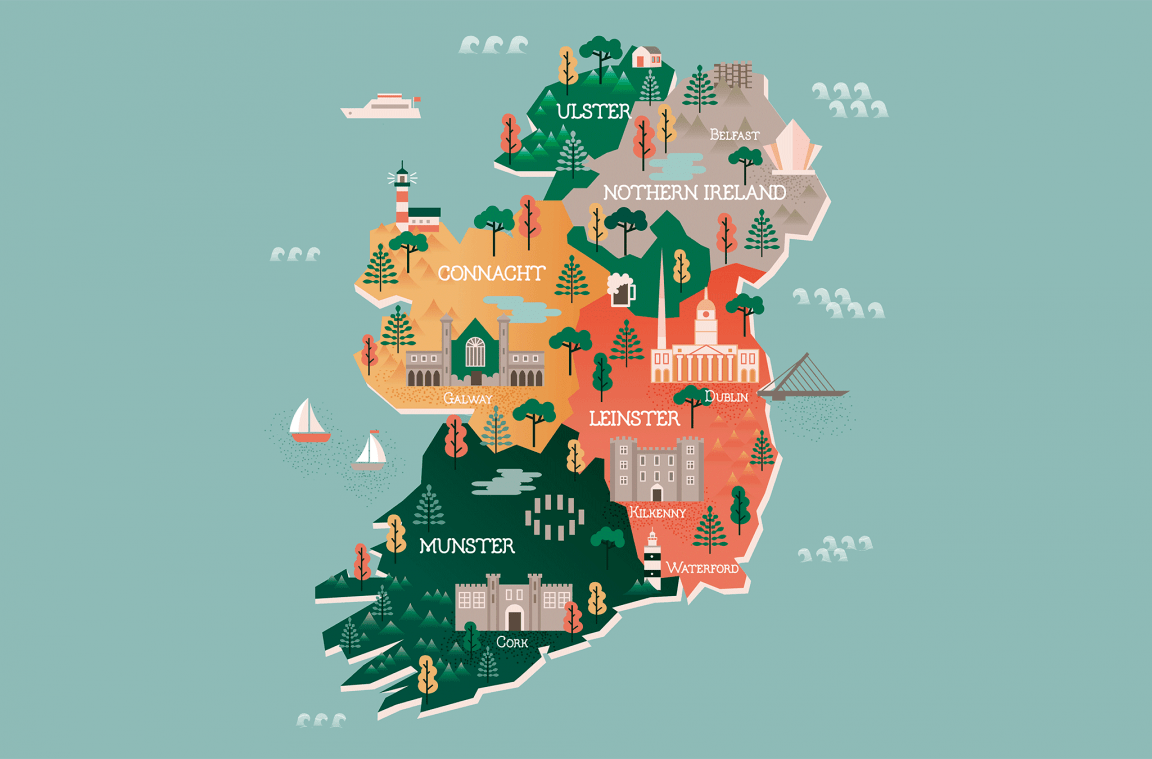

Irish history took a dramatic turn in 795 CE with the first recorded Viking raid on Rathlin Island. For the next two centuries, Norse raiders targeted Ireland’s wealthy monasteries, initially focusing on quick raids before eventually establishing permanent settlements. These Vikings founded or expanded many of Ireland’s first towns, including Dublin (originally “Dubh Linn,” meaning “black pool”), Waterford, Wexford, Cork, and Limerick.

Despite their reputation for violence, the Vikings eventually integrated into Irish society, creating a hybrid Norse-Gaelic culture that influenced trade, politics, and art. Their maritime expertise connected Ireland more closely with European and Mediterranean trade networks, introducing new goods and ideas that enriched Irish history.

The Battle of Clontarf in 1014 represents a significant milestone in Irish history. High King Brian Boru defeated a Viking-Irish alliance but died during the conflict. While often portrayed as Ireland expelling Viking influence, the reality was more complex – Norse settlements continued, but increasingly under Irish political control.

Norman involvement in Irish history began in 1169 when Dermot MacMurrough, the deposed King of Leinster, invited Norman knights from Wales to help him reclaim his kingdom. This initial small force of Norman adventurers, led by Richard de Clare (Strongbow), quickly conquered large territories with their superior military technology.

Concerned about Strongbow’s growing power, King Henry II of England arrived in 1171 with a larger army, asserting royal authority over both the Norman lords and Irish kingdoms. This intervention established an English royal claim to authority in Ireland that would shape Irish history for centuries to come.

The Normans transformed Ireland’s physical landscape by constructing stone castles, establishing towns with protective walls, and reorganizing agricultural land. Their architectural legacy remains visible throughout Ireland, with structures like Trim Castle and King John’s Castle representing the Norman impact on Irish history.

Medieval Ireland: Anglo-Irish Relations (1200 – 1500 CE)

The Norman conquest initiated a complex period in Irish history characterized by cultural hybridization and shifting political loyalties. Many Norman families, including the powerful FitzGeralds (Earls of Kildare) and Butlers (Earls of Ormond), became “more Irish than the Irish themselves,” adopting Gaelic customs, language, and laws while maintaining their distinct identity.

By the 13th century, Irish history showed a divided society: the area around Dublin (known as the Pale) remained under direct English control, while the rest of the country operated under varying degrees of Gaelic resurgence and Norman-Irish autonomy. The Bruce invasion of 1315-1318, when Edward Bruce (brother of Scottish king Robert) claimed the Irish high kingship, further destabilized Anglo-Irish relations.

The arrival of the Black Death in 1348 devastated Ireland’s population, particularly in urban areas, causing economic decline and allowing Gaelic Irish kingdoms to reclaim territories previously lost to the Normans. This demographic catastrophe changed the trajectory of Irish history for generations.

The Statutes of Kilkenny (1366) attempted to prevent cultural assimilation by forbidding the Anglo-Irish from speaking Irish, wearing Irish clothes, or following Irish customs. These laws, largely unenforceable beyond the Pale, highlight the Crown’s concern about losing control over its Irish territories – a recurring theme in Irish history.

By the late medieval period, English royal authority in Ireland had declined significantly. The powerful Earl of Kildare functioned as the king’s deputy but operated with considerable independence, exemplifying the feudal autonomy that characterized this phase of Irish history. Meanwhile, Gaelic lords maintained traditional political systems in their territories, creating a complex patchwork of jurisdictions across the island.

Tudor Conquest and Plantation Era (1500 – 1700)

The Tudor dynasty brought renewed English determination to control Ireland, fundamentally altering the course of Irish history. Henry VIII’s break with Rome had profound consequences for Irish politics, as most Irish leaders, both Gaelic and Anglo-Irish, remained Catholic. Religious difference now added a new dimension to political conflicts.

The policy of “surrender and regrant” required Irish lords to surrender their lands to the crown and receive them back as royal grants, exchanging traditional Brehon law claims for English legal titles. This strategy aimed to integrate the Irish nobility into the English system but often created confusion over land ownership that would complicate Irish history for centuries.

A series of rebellions challenged Tudor rule, including the Desmond Rebellions (1569-1573 and 1579-1583) and the Nine Years’ War (1593-1603) led by Hugh O’Neill and Hugh O’Donnell. These conflicts marked a crucial turning point in Irish history, as O’Neill’s defeat at the Battle of Kinsale (1601) effectively ended the old Gaelic order.

The plantation system – the confiscation of land from Irish Catholics and its redistribution to Protestant settlers from England and Scotland – transformed Ireland’s demographic, religious, and cultural landscape. The Plantation of Ulster (1609) was particularly extensive and successful, creating a Protestant majority in the northern counties that continues to influence Irish history today.

The Irish Confederate Wars (1641-1653), part of the broader Wars of the Three Kingdoms, saw Catholic Ireland initially rise against Protestant settlers before becoming entangled in the English Civil War. Oliver Cromwell’s brutal campaign in Ireland (1649-1650) remains one of the most controversial episodes in Irish history, with massacres at Drogheda and Wexford and widespread land confiscation further entrenching sectarian divisions.

The Williamite War (1688-1691) represented the final major conflict of this tumultuous period. James II’s Catholic forces were defeated by William of Orange’s army at the Battle of the Boyne (1690), securing Protestant ascendancy in Ireland. The subsequent Treaty of Limerick, whose terms were largely ignored, and the Penal Laws against Catholics, created deep grievances that would influence Irish history for generations.

18th Century Ireland: Penal Laws and Parliamentary Politics

The 18th century opened with Ireland firmly under Protestant control, with the native Catholic majority subjected to the Penal Laws. These restrictions barred Catholics from voting, holding public office, owning weapons, receiving education, and inheriting or purchasing land. This systematic discrimination represents one of the most oppressive chapters in Irish history.

Despite these challenges, Irish history during this period wasn’t exclusively defined by oppression. The Protestant-dominated Irish Parliament gradually asserted greater independence from Britain, particularly after 1782 when Henry Grattan secured legislative freedom. “Grattan’s Parliament” operated during a period of relative prosperity for the Anglo-Irish ascendancy, whose architectural legacy includes Dublin’s magnificent Georgian streets and squares.

Economic changes significantly shaped Irish history during this era. The linen industry flourished in Ulster, while pastoral farming dominated elsewhere. However, increasing subdivision of land among the Catholic peasantry created a precarious dependency on potato cultivation that would have catastrophic consequences in the following century.

The 1798 Rebellion, inspired by the American and French Revolutions and led by the Society of United Irishmen, sought to establish an independent, non-sectarian Irish republic. Though unsuccessful, this uprising represents a crucial moment in Irish history, particularly through its leader Theobald Wolfe Tone, who is often considered the father of Irish republicanism.

The rebellion’s failure led directly to the 1800 Act of Union, which abolished the Irish Parliament and integrated Ireland fully into the United Kingdom. This constitutional change, implemented through significant bribery and without Catholic support, created the political framework that would define Irish history for the next 120 years.

19th Century: The Great Famine and Irish History Transformation

The campaign for Catholic Emancipation, led by Daniel O’Connell (“The Liberator”), achieved success in 1829, allowing Catholics to sit in parliament. O’Connell’s mass political mobilization through monster meetings demonstrated the potential power of peaceful agitation and established important precedents in Irish history for constitutional nationalism.

The Great Famine (1845-1852) represents the most catastrophic event in modern Irish history. When potato blight destroyed the crop that fed nearly half the population, approximately one million people died from starvation and related diseases, while another million emigrated. The British government’s inadequate response – adhering to laissez-faire economic principles and ending relief measures prematurely – created lasting bitterness that continues to influence interpretations of Irish history.

The Famine accelerated emigration that had already begun, creating a global Irish diaspora, particularly in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Britain. This diaspora would play a crucial role in supporting Irish nationalist movements and preserving Irish cultural identity, forming an important international dimension to Irish history.

Land agitation dominated the latter half of the 19th century, with the Irish National Land League (founded 1879) fighting for “the three Fs”: fair rent, fixity of tenure, and free sale. This mass movement, combining agrarian and national concerns under leaders like Michael Davitt and Charles Stewart Parnell, represents a key development in Irish history by mobilizing the rural population for political action.

The question of Home Rule – self-government for Ireland while remaining within the United Kingdom – dominated late 19th century politics. Parnell’s parliamentary alliance with British Liberal Prime Minister William Gladstone brought Ireland close to achieving this goal, but bills failed in 1886 and 1893. These failures, along with the Parnell divorce scandal that split the nationalist movement, created frustration that would eventually lead to more radical approaches in Irish history.

Revolutionary Period: The Fight for Independence (1900 – 1922)

The early 20th century saw cultural nationalism flourish through organizations like the Gaelic League (founded 1893) and the Gaelic Athletic Association (founded 1884), which revived interest in the Irish language and traditional sports. This “Gaelic Revival” also influenced literature, with writers like W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory drawing on Irish mythology and folklore, creating a cultural renaissance that enriched Irish history.

The Home Rule crisis intensified with the introduction of a third bill in 1912. Ulster Unionists, opposed to governance from Dublin, formed the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) to resist implementation. In response, Irish nationalists established the Irish Volunteers. Civil war seemed imminent until World War I temporarily suspended the crisis, marking a crucial turning point in Irish history.

The Easter Rising of 1916, though initially unpopular due to wartime casualties, transformed Irish history when British authorities executed its leaders, including Patrick Pearse and James Connolly. These executions galvanized public opinion toward separatist nationalism rather than the Home Rule compromise that had previously dominated discourse.

The 1918 general election resulted in a landslide victory for Sinn Féin, whose MPs refused to take seats at Westminster and instead established Dáil Éireann (Irish Assembly) in Dublin, declaring independence. This pivotal election fundamentally altered the direction of Irish history by giving democratic legitimacy to the separatist cause.

The Irish War of Independence (1919-1921) saw the Irish Republican Army (IRA) wage a guerrilla campaign against British forces, while the Dáil operated as a parallel government. Violence escalated with events like Bloody Sunday (November 1920), when 14 British intelligence officers were assassinated, followed by British forces firing on a crowd at a Gaelic football match, killing 14 civilians.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921 ended the conflict by creating the Irish Free State, a self-governing dominion within the British Empire comprising 26 of Ireland’s 32 counties. Northern Ireland, with its Protestant majority, remained part of the United Kingdom. This partition, intended as temporary, became a defining and contentious feature of modern Irish history.

Modern Ireland: From Civil War to Celtic Tiger (1922 – Present)

The Treaty’s terms, particularly the required oath of allegiance to the British monarch, split the independence movement. The resulting Irish Civil War (1922-1923) pitted former comrades against each other, with the pro-Treaty forces ultimately prevailing but leaving bitter divisions that would shape Irish politics for decades – one of the most painful chapters in Irish history.

Under Éamon de Valera’s leadership, Ireland gradually dismantled its constitutional links with Britain, introducing a new constitution in 1937 and declaring a republic in 1949. Northern Ireland remained part of the UK, with its Catholic minority experiencing discrimination in housing, employment, and political representation, creating grievances that would later fuel conflict.

The Troubles (1968-1998) began as a civil rights movement before escalating into sectarian violence that claimed over 3,500 lives. This traumatic period in Irish history saw paramilitary campaigns, British military deployment, internment without trial, hunger strikes, and bombings that affected communities across Northern Ireland and beyond.

The Good Friday Agreement (1998) established power-sharing institutions and recognized that Northern Ireland’s constitutional status could only change with majority consent, bringing relative peace and creating new frameworks for North-South and British-Irish relations. This landmark peace process represents one of the most positive developments in recent Irish history.

Meanwhile, the Republic of Ireland transformed from an economically underdeveloped, largely agricultural society into a modern European nation. EU membership (1973) brought structural funds that developed infrastructure, while educational investments and favorable tax policies attracted multinational corporations. The resulting economic boom of the 1990s-2000s, dubbed the “Celtic Tiger,” dramatically raised living standards and reversed emigration patterns that had characterized much of Irish history.

The 2008 financial crisis severely impacted Ireland, necessitating an international bailout. However, economic recovery has been impressive, demonstrating resilience that reflects the adaptability evident throughout Irish history. Contemporary Ireland has become increasingly progressive, voting for marriage equality (2015) and repealing constitutional restrictions on abortion (2018), representing significant social evolution.

Top 7 Historical Sites Every Visitor Must Experience

- Newgrange (County Meath): This 5,200-year-old passage tomb predates the Egyptian pyramids and represents one of the most impressive prehistoric monuments in Europe. Its remarkable winter solstice alignment demonstrates the astronomical knowledge of Ireland’s earliest inhabitants, providing a tangible connection to ancient Irish history.

- Rock of Cashel (County Tipperary): This spectacular collection of medieval buildings set on a limestone outcrop includes a round tower, Romanesque chapel, Gothic cathedral, and castle. Associated with the kings of Munster and St. Patrick, it encapsulates multiple periods of Irish history in one stunning location.

- Kilmainham Gaol (Dublin): This former prison housed many leaders of Irish rebellions, including those executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Now a museum, it provides powerful insight into Ireland’s revolutionary period and the struggle for independence, representing a somber but essential site for understanding modern Irish history.

- Trinity College Dublin: Founded in 1592, Trinity houses the magnificent Book of Kells and the stunning Long Room Library. As Ireland’s oldest university, it has played a central role in the country’s intellectual history and counts many significant figures in Irish history among its alumni.

- Clonmacnoise (County Offaly): This early Christian site founded by St. Ciarán in the 6th century includes the ruins of a cathedral, seven churches, two round towers, and high crosses. It exemplifies Ireland’s monastic heritage and the “Land of Saints and Scholars” period of Irish history.

- Bunratty Castle and Folk Park (County Clare): The most complete medieval fortress in Ireland, Bunratty offers visitors the opportunity to experience both a 15th-century castle and a reconstructed 19th-century village, providing insight into multiple periods of Irish history and everyday life.

- GPO Witness History (Dublin): Located in Dublin’s General Post Office, headquarters of the 1916 Easter Rising, this immersive exhibition uses interactive elements to tell the story of this pivotal event in Irish history and the birth of the modern Irish nation.

Irish History Timeline: 10 Pivotal Moments That Shaped the Nation

- 8000 BCE: First human settlements in Ireland mark the beginning of Irish history.

- 3200 BCE: Construction of Newgrange passage tomb, demonstrating sophisticated astronomical knowledge.

- 432 CE: Traditional date of St. Patrick’s arrival, beginning Christianity’s transformative influence on Irish history.

- 1169 CE: Norman invasion establishes English involvement in Ireland that would last for centuries.

- 1541: Henry VIII declares himself King of Ireland, intensifying Tudor conquest.

- 1649-50: Cromwellian conquest devastates Catholic Ireland, resulting in massive land confiscations.

- 1845-52: The Great Famine kills one million and forces another million to emigrate, irreversibly altering Irish history.

- 1916: Easter Rising sparks the revolutionary period leading to independence.

- 1922: Irish Free State established following the Anglo-Irish Treaty, partitioning the island.

- 1998: Good Friday Agreement brings peace to Northern Ireland after decades of conflict.

Experiencing Irish History Today

Today’s Ireland offers visitors numerous ways to engage with its rich historical heritage. Museums like the National Museum of Ireland and EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum provide comprehensive overviews of Irish history, while heritage sites across the country offer immersive experiences at authentic historical locations.

Walking tours in cities like Dublin, Cork, and Galway allow visitors to discover urban history with knowledgeable local guides, while historical reenactments at sites like Bunratty Castle bring the past vividly to life. Traditional music sessions in pubs offer not just entertainment but connection to Ireland’s cultural heritage, with songs often telling stories from Irish history.

Ireland’s historical landscapes remain remarkably intact, from Stone Age monuments to medieval castles to Georgian architecture. The country’s compact size means visitors can experience multiple periods of Irish history within short distances, making it an ideal destination for history enthusiasts.

As you plan your Irish journey, consider exploring beyond the famous landmarks to discover hidden gems that illuminate lesser-known aspects of Irish history. Whether following the trail of saints and scholars, exploring Viking heritage in coastal towns, or engaging with the complex legacy of the revolutionary period, Ireland offers historical experiences to match every interest.

For those seeking to understand their Irish ancestry, genealogical resources are widely available, including at the National Library of Ireland and local heritage centers throughout the country. Connecting personal family stories to the broader sweep of Irish history provides many visitors with particularly meaningful travel experiences.

Ireland’s history isn’t merely preserved in museums and monuments—it lives in the stories, music, and traditions of its people. By engaging with local communities during your visit, you’ll gain deeper insight into how historical events continue to shape Irish identity and culture today, making your journey through Irish history truly unforgettable.